Hello!

This blog is a direct response given to at ask assigned by Dr. Dilip Barad, under the study of a contemporary novel, 'gun Island'

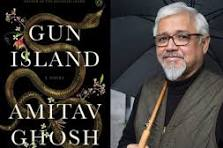

Amitav Ghosh is an Indian author celebrated for his novels that blend history, culture, and storytelling. Born on July 11, 1956, Ghosh's works include "The Circle of Reason" and "The Ibis Trilogy," known for its exploration of globalization and colonialism. His writing is marked by meticulous research and a keen eye for detail. Ghosh's contributions to literature have earned him prestigious awards such as the Sahitya Akademi Award and the Padma Shri.

How does this novel develop your understanding of a rather new genre known as 'cli-fi'?

Science fiction (often abbreviated as sci-fi) is a genre of speculative fiction that explores imaginative concepts derived from science and technology. It often depicts futuristic or alternative realities, posing "what if" questions about the impact of scientific advancements, societal changes, or extraterrestrial encounters on human life and civilization. Science fiction can encompass a wide range of themes and settings, including space exploration, time travel, artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, dystopian societies, and alien civilizations.

"Gun Island" by Amitav Ghosh is a novel that intricately weaves together themes of climate change, environmental degradation, and human adaptation. Here's a detailed breakdown of how it develops our understanding of the cli-fi genre:

Scientific Context and Realism: Ghosh incorporates accurate scientific information and real-world examples of climate change impacts, grounding the narrative in scientific reality. From discussions about melting glaciers to the effects of sea-level rise on coastal communities, the novel presents a detailed and nuanced portrayal of environmental issues.

Personal Narrative and Emotional Impact: Through the protagonist, Deen, and other characters, Ghosh explores the emotional toll of climate change on individuals and communities. Deen's journey from skepticism to acceptance of the reality of climate change reflects a common experience shared by many people today. By focusing on personal narratives, Ghosh humanizes the climate crisis, making it more relatable and emotionally resonant for readers.

Historical and Mythical Context: Ghosh skillfully interweaves historical events and myths with contemporary environmental concerns. By drawing parallels between past catastrophes, such as the Great Bengal Famine, and current environmental challenges, Ghosh highlights the cyclical nature of human-induced crises. Additionally, the incorporation of myths and legends adds depth to the narrative, emphasizing the timeless significance of humanity's relationship with the natural world.

Global Perspective and Intersectionality: "Gun Island" takes readers on a journey across continents, from India to the United States and Italy, underscoring the global nature of climate change. Through diverse characters and settings, Ghosh explores the intersectionality of environmental issues with other social, political, and economic factors. He highlights how climate change exacerbates existing inequalities and injustices, particularly affecting marginalized communities.

How does Amitav Ghosh use the myth of the Gun Merchant ['Bonduki Sadagar'] & Manasa Devi to initiate discussion on the issues of climate change, migration, the refugee crisis, and human trafficking?

The myth of the Gun Merchant serves as a metaphor for the ecological imbalance caused by human actions. Ghosh draws parallels between the ancient tale of environmental destruction and the modern-day challenges of climate change, deforestation, and habitat loss. By exploring the consequences of disrupting the natural order, Ghosh highlights the urgent need for environmental conservation and sustainable practices.

Through the protagonist Deen's encounters with refugees and displaced communities, Ghosh addresses the human consequences of environmental degradation. The myth of the Gun Merchant reflects the timeless theme of displacement, as people are forced to flee their homes due to natural disasters, rising sea levels, and other environmental pressures. Ghosh sensitively portrays the experiences of migrants and refugees, shedding light on their struggles and resilience in the face of adversity. Ghosh links the myth of Manasa Devi, the goddess of snakes and fertility, to the plight of refugees seeking sanctuary and security. Like the serpent in the myth, refugees are often marginalized and demonized, facing discrimination and hostility as they search for safety. Ghosh challenges stereotypes and misconceptions about refugees, emphasizing their humanity and the moral imperative to offer compassion and assistance.

The narrative of "Gun Island" also delves into the darker aspects of migration, including human trafficking and exploitation. Ghosh highlights the vulnerabilities of migrants, particularly women and children, who are at risk of being trafficked and subjected to abuse and exploitation. Through the characters' experiences, Ghosh confronts the realities of human trafficking and calls attention to the need for greater awareness and action to combat this pervasive issue.

How does Amitav Ghosh make use of the 'etymology' of common words to sustain mystery and suspense in the narrative?

Amitav Ghosh likes to use where words come from to make his stories more interesting. In "Gun Island," there's a name, "Bonduki Sadagar," that people think means "Gun Merchant." But as the main character, Deen, investigates, he finds out it might mean something different. He learns that the old Arabic name for Venice was similar to "Bonduki," and it was also linked to the word for guns.

This discovery makes the story more exciting because it changes what people thought the name meant. Instead of just being about a person who sells guns, it could mean "the Merchant who went to Venice." This new idea shifts how Deen looks into things and adds a bit of suspense, making readers want to find out more about the characters and their pasts.

What are your views on the use of myth and history in the novel Gun Island to draw the attention of the reader towards contemporary issues like climate change and migration?

In his narratives, Amitav Ghosh often uses the origins of common words to create deeper layers of meaning and intrigue. In "Gun Island," he delves into the etymology of the name "Bonduki Sadagar," initially believed to mean "Gun Merchant." This linguistic exploration serves to maintain suspense in the story. As the protagonist, Deen, investigates the name's origins, he discovers that the old Arabic name for Venice was al-Bunduqevya, also associated with guns.

This revelation introduces ambiguity and fascination into the narrative. The initial assumption about the name is challenged, and a new interpretation emerges - "the Merchant who went to Venice." This change in understanding alters the course of Deen's investigation and adds suspense, keeping readers engaged in uncovering the mysteries surrounding the characters and their pasts.

By weaving the etymology of common words into the plot, Ghosh not only sustains suspense but also highlights the interconnectedness of language, history, and the story's themes. This literary device enriches the storytelling, encouraging readers to actively decode the layers of meaning within the words and enhancing the overall depth of the narrative experience.

Is there any connection between 'The Great Derangement' and 'Gun Island'?

Yes, there is a strong connection between "The Great Derangement" and "Gun Island," both authored by Amitav Ghosh. "The Great Derangement' is a non-fiction work in which Ghosh explores the cultural and literary implications of climate change, arguing that literature has largely failed to address this urgent global issue. On the other hand, "Gun Island" is a novel that incorporates themes of climate change, migration, and environmental degradation into its fictional narrative. Both works deal with the theme of climate change and its impact on human societies and the natural world. "The Great Derangement" approaches this theme from a non-fiction perspective, analyzing the historical, cultural, and literary reasons for society's failure to adequately address climate change. "Gun Island," on the other hand, explores the consequences of climate change through a fictional story set in contemporary times.

While "The Great Derangement" provides a theoretical and critical analysis of climate change discourse, "Gun Island" delves into the human experience of environmental upheaval. The novel vividly depicts the consequences of climate change on individuals and communities, highlighting the displacement of people, the loss of traditional ways of life, and the destruction of natural habitats.

Both works integrate literature and environmental themes, albeit in different ways. "The Great Derangement" examines the absence of climate change narratives in literature and the challenges of representing such a complex phenomenon. "Gun Island," on the other hand, incorporates environmental themes into its fictional narrative, using storytelling as a means to explore the emotional and psychological dimensions of climate change.

Thank You!